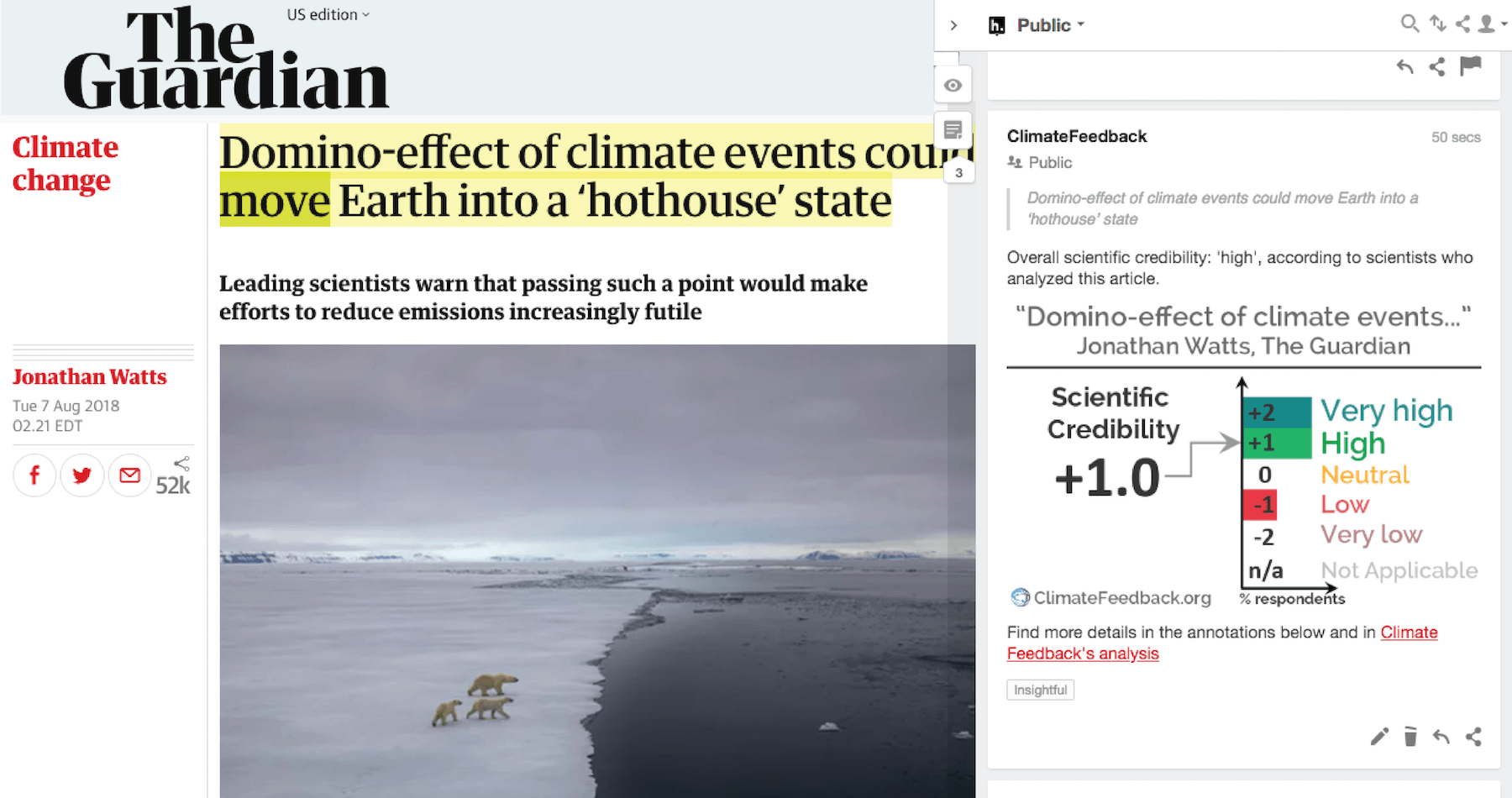

Five scientists analyzed the article and estimate its overall scientific credibility to be 'high'. more about the credibility rating

A majority of reviewers tagged the article as: Insightful.

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

SUMMARY

This article in The Guardian covers an essay published by a group of scientists in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The paper describes previously existing research but discusses the possibility that feedbacks could commit Earth’s climate to long-term warming even if human-caused emissions ceased.

Scientists who reviewed the article found that it explained the article fairly accurately, with some subtle exceptions. The potential warming due to greenhouse gases released from permafrost, for example, is misstated as 0.9 °C—ten times the correct number of 0.09 °C. The article could also make it clearer for the reader that the essay relates to future warming that could take hundreds or even thousands of years to fully materialize.

See all the scientists’ annotations in context. You can also install the Hypothesis browser extension to read the scientists’ annotations in context.

REVIEWERS’ OVERALL FEEDBACK

These comments are the overall assessment of scientists on the article, they are substantiated by their knowledge in the field and by the content of the analysis in the annotations on the article.

Andrew MacDougall, Assistant Professor, St. Francis Xavier University:

The article reasonably summarizes a new study published in PNAS, which describes the potential of tipping elements to enhance climate warming and the potential for the Earth to transition into a hot-house climate state. The article is careful to point out uncertainties and thus avoids being sensational. However, there are many small errors scattered throughout the article. For example, the strength of the permafrost carbon feedback is given as 0.9 °C instead of 0.09 (0.04 to 0.16) °C. Other examples include referring to Arctic sea-ice as the “Arctic ice sheet”, and attributing the permafrost feedback to release of methane instead of primarily a release of CO2.

Richard Betts, Professor, Met Office Hadley Centre & University of Exeter:

The two important flaws in the article are that:

1) It does not make clear that the timescales involved in these feedbacks becoming large are very long—the paper says centuries to millennia. This is compounded by a mistake in one of the numbers quoted (permafrost feedback should be 0.09 °C by 2100 according to the paper, but the article writes this as 0.9 °C).

2) The article ramps up the certainty of the scenario, using “will” where the paper uses “could” in several places.

Pepijn Bakker, Assistant professor, Department of Earth Sciences, Vrije Universiteit, Netherlands:

No inaccuracies and a good, balanced article with some notes on the uncertainties of the work in question, and remarks from scientists that were not involved in the paper.

Katrin Meissner, Professor, University of New South Wales:

The article fairly represents the main conclusions of the PNAS paper.

Alexis Berg, Research Associate, Harvard University:

This article does a decent job reporting on a recent scientific paper. Admittedly it’s a tricky article to report on. The original article in PNAS asks the question whether a “2°C warmer” climate will actually be there if we reduce CO2 emissions enough to be in line with such a warming target according to our current understanding of the climate system and to current climate model projections. The key distinction is that IPCC projections do suggest that for some emission trajectories, global mean temperature stabilizes at +2°C.

However, certain feedback loops are not routinely accounted for in climate models yet (e.g., permafrost melting), and the time horizon of projections is usually limited to 2100 – certain feedbacks might kick in after that. So, the authors of the PNAS paper are saying: there is small possibility that +2°C is actually not stable and ultimately the system will slip away. However, there don’t really bring up any new evidence. It’s really more a discussion piece.

I think the Guardian article could have done a slightly better job conveying the level of uncertainty of the PNAS paper and explaining the difference between the PNAS authors’ conjecture and current climate model projections.

Notes:

[1] See the rating guidelines used for article evaluations.

[2] Each evaluation is independent. Scientists’ comments are all published at the same time.

ANNOTATIONS

The statements quoted below are from the article; comments are from the reviewers (and are lightly edited for clarity).

Richard Betts, Professor, Met Office Hadley Centre & University of Exeter:Domino-effect of climate events could move Earth into a ‘hothouse’ state

“Move into” makes it sound sudden, but the paper suggests that, although the feedbacks could be triggered soon and become self-perpetuating, they could take centuries to millennia to take full effect.

More accurate content would warrant a revised title, eg “Domino-effect of climate events could set Earth on path towards a ‘hothouse’ state”.

Richard Betts, Professor, Met Office Hadley Centre & University of Exeter:The authors of the essay, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, stress their analysis is not conclusive

I think “not conclusive” is still too certain based on the actual level of confidence in the paper. I’d say “tentative” would reflect the paper more accurately. For example, the paper uses the term “risk averse approach” for the proposed 2°C threshold, and says “we cannot exclude the risk…”. It also use caveated language such as “could” and “may” a lot, and talk of “probability … difficult to quantify”.

Andrew MacDougall, Assistant Professor, St. Francis Xavier University:This grim prospect is sketched out in a journal paper that considers the combined consequences of 10 climate change processes, including the release of methane trapped in Siberian permafrost

The permafrost carbon cycle feedback results from the decay of organic matter (remains of dead plants) previously frozen in permafrost soils. Carbon can be released either as CO2 or methane depending on the conditions of the soil, however the strength of the feedback, especially on long time-scales, is expected to come mostly from the release of CO2.

Richard Betts, Professor, Met Office Hadley Centre & University of Exeter:Their new paper asks whether the planet’s temperature can stabilise at 2°C or whether it will gravitate towards a more extreme state.

My reading of the paper is that it’s the other way round—it asks whether it would stabilize at 2°C or *could* gravitate towards a more extreme state. The paper is clear that this is about risk, not certainty, and that the proposed 2°C threshold represents a “risk averse approach”

Richard Betts, Professor, Met Office Hadley Centre & University of Exeter:Previous studies have shown that weakening carbon sinks will add 0.25°C, forest dieback will add 0.11°C, permafrost thaw will add 0.9°C and increased bacterial respiration will add 0.02°C.

The paper uses “could” not “will”. (See Table 1.)

The paper also says 0.09°C [for additional warming caused by permafrost thaw] not 0.9°C

Katrin Meissner, Professor, University of New South Wales:We note that the Earth has never in its history had a quasi-stable state that is around 2C warmer than the preindustrial and suggest that there is substantial risk that the system, itself, will ‘want’ to continue warming because of all of these other processes – even if we stop emissions,” she said. “This implies not only reducing emissions but much more.”

This can be refined to: A stable state with today’s CO2 concentrations (or higher) is not compatible with a 1.5-2°C warming above preindustrial levels. As stated in the supplementary material, “Current atmospheric CO2 concentration has already reached the lower bound of mid-Pliocene levels (Table S1), an eventual sea-level rise of up to 10 m or more is likely unless CO2 emissions are rapidly reduced and widespread CO2 removal from the atmosphere is deployed.” Mid-Pliocene temperature levels were likely higher than the Paris target.

Richard Betts, Professor, Met Office Hadley Centre & University of Exeter:The heatwave we now have in Europe is not something that was expected with just 1C of warming

This may reflect his personal view, but I don’t think this statement reflects the views of the meteorological community. Climate change has probably made the heatwave hotter than it would have been, but I’ve not seen any analysis suggesting that the additional impact of climate change on the heatwave is larger than would be expected from the 1°C global warming that we’ve seen so far.

Richard Betts, Professor, Met Office Hadley Centre & University of Exeter:[…]but to state that 2C is a threshold we can’t pull back from is new, I think. I’m not sure what ‘evidence’ there is for this

I agree with this cautionary note—the paper bases the 2°C threshold on previous papers that themselves are reviews, and the paper says this is a “risk averse” approach.